Have you ever watched someone cross themselves and noticed something a little different? Maybe the motion felt familiar yet not quite the same? That small, powerful gesture—the Sign of the Cross—is a deeply meaningful tradition for both Catholics and Orthodox Christians. But the way each group performs it tells a story that stretches back nearly a thousand years.

Today, we’ll explore why Catholics and Orthodox Christians make the Sign of the Cross differently—and why this ancient distinction still matters.

A Symbol Rooted in the Origins of Christianity

The Sign of the Cross is much more than a simple movement; it’s a prayer in motion. Each time believers cross themselves, they are invoking the Holy Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—and remembering Christ’s sacrifice for humanity.

But hidden behind this familiar gesture is a fascinating story, one tied directly to the Great Schism of 1054, the historic split that divided Christianity into Eastern (Orthodox) and Western (Catholic) branches. Over time, even the smallest of differences—like how believers bless themselves—became powerful symbols of identity, almost like a secret handshake between East and West.

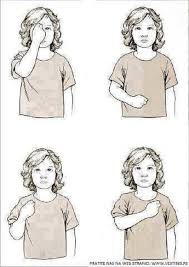

How Orthodox Christians Make the Sign of the Cross

Walk into an Orthodox Church, and you’ll notice a very different style—one that’s far more deliberate and loaded with theological meaning:

The thumb, index, and middle fingers are joined together to symbolize the Holy Trinity.

The ring finger and little finger are tucked against the palm, representing Christ’s divine and human natures.

The motion is from the forehead to the upper abdomen, then right shoulder to left shoulder.

The Orthodox way is almost like a visual sermon—a constant, visible reminder of central Christian beliefs. Even the right-to-left movement has a deep meaning: Christ, after His resurrection, is seated at the right hand of the Father.

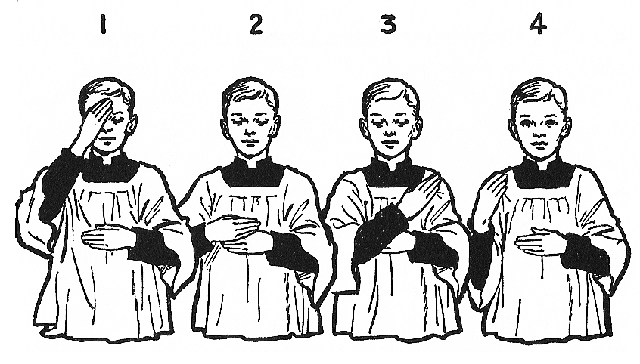

How Catholics Make the Sign of the Cross

For most Roman Catholics, the Sign of the Cross is performed with an open hand, or sometimes with three fingers together. The motion goes like this:

Forehead

Chest

Left shoulder

Right shoulder

Simple, right?

This left-to-right motion has its own deep symbolism. Many Catholics interpret it as moving from darkness to light, from sin to grace, although this explanation isn’t always taught formally.

Why This Ancient Difference Still Matters

You might wonder—does this difference really matter today? The short answer is yes, but not in a divisive way.

Before the Great Schism, early Christians likely crossed themselves in various ways. After the split between Rome and Constantinople, small customs like this hardened into markers of identity. By around 1200 AD, even Pope Innocent III noted that Catholics typically crossed themselves left to right, suggesting the practice had already settled into tradition in the West.

And here’s an interesting twist: Eastern Catholics—such as Ukrainian Greek Catholics, Melkites, and Maronites—are in full communion with Rome but often continue to cross themselves like the Orthodox: right to left, with the three-finger technique!

This diversity within Catholicism shows the richness of the Christian tradition: ancient practices adapted by different cultures, but all tied together by the same faith.

No Matter the Direction, the Heart Remains the Same

At the end of the day, whether the Sign of the Cross is made left-to-right or right-to-left, with open hands or three fingers, the heart of the prayer stays the same:

“In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

This small, powerful gesture is a daily companion for millions of people—before meals, when passing by a church, or when seeking a moment of divine protection or peace. It’s a living link to centuries of faith, history, and tradition.

Conclusion:

The next time you see someone cross themselves differently, remember: you’re witnessing a living piece of Christian history—a thousand-year-old story told in a single, graceful motion.