History of the Serbian Orthodox Church

The history of the Serbian Orthodox Church covers the history of Orthodox Christianity among the Serbs, specifically the history of the Serbian Orthodox Church as a local church in the Serbian lands. The history of Orthodox Christianity in the Serbian lands begins with the Christianization of the Serbs, which took place between the 7th and 10th centuries, and continues with the development and growth of Serbian church institutions. From the early 11th to the early 13th century, these institutions were under the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Ohrid. The most significant turning point in the history of the Serbian Orthodox Church occurred in 1219, when the Orthodox Church in Serbia became autocephalous and was organized as the Serbian Archbishopric, led by its own archbishop. After the declaration of the Serbian Empire, it was elevated to the rank of the Serbian Patriarchate in 1346. However, after 1463, the patriarchal throne remained vacant for the next fifty years, and efforts for restoration eventually succeeded in 1557.

During the period of Turkish rule, the restored Serbian Patriarchate played a key role in the survival of the Serbian people. It was abolished in 1766 by the Phanariots in Constantinople. Meanwhile, in the Serbian lands under Habsburg rule, the self-governing Metropolitanate of Karlovci was established, which was elevated to the honorary rank of the Serbian Patriarchate in Sremski Karlovci in 1848. The Orthodox Church in restored Serbia gained autonomy in 1831 as the autonomous Metropolitanate of Belgrade, which became autocephalous in 1879. The situation of other Serbian church regions and dioceses in Montenegro, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Raška, Kosovo, Metohija, and Vardar was also unique. All the Serbian church regions united in 1920 into a single Serbian Patriarchate, which is now known as the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Christianization of the Serbs

When the Slavic tribes, including the Serbs, arrived in the Southeast European region during the 6th and 7th centuries, they encountered remnants of early Christian heritage in the areas of the decayed late Roman (early Byzantine) provinces. The process of Christianization of the South Slavs took place gradually and unfolded in several stages. The Christianization of the Serbs began during the 7th and 8th centuries and was largely completed during the 9th and 10th centuries. With the successful Christianization of the Serbs, the foundation for the emergence and development of Serbian Christianity was laid, embodied in the Serbian Orthodox Church.

From the moment they arrived on the Balkan Peninsula, the Serbs were exposed to the strong influence of Christianity. The adoption of Christianity was an extremely long process, as evidenced by the records of the Christianization of Serbian tribes from the 7th century and the second half of the 9th century.

Studying this subject comes with a major challenge—the lack of sources. The primary, and almost sole, sources dealing with this issue are: The List of Nations, the Panegyric to Basil I, and the Tactics of Emperor Leo VI. The List of Nations, written by Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos, is considered a highly significant work for studying the history of the Slavs’ arrival on the Balkan Peninsula. Porphyrogennetos mentions how Emperor Heraclius sent priests from Rome to Serbia, marking one of the earliest contacts between the Serbs and Christianity. In addition to these sources, three letters provide essential information about the Serbs and their Christianization from this period: the letter of Pope Agatho to Emperor Constantine IV from 680, the letter of Pope John X to the Dalmatian bishop, and the letter of Pope John VIII to the Serbian prince Mutimir from 873.

When the Serbs arrived on the Balkan Peninsula, they were pagans, worshiping their own gods. It is only from the 6th century that we can speak about the beginnings of their Christianization under the influence of Byzantium. The Serbs who converted to Christianity in this period were mostly those temporarily serving the Byzantine Empire or living under the rule of the Roman Emperor. Christianization became more pronounced in the 8th century. The scale of this Christianization during this period is evident from the fact that in 766, a Slav named Niketas was elected as the Ecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople. The first record of a Serbian leader converting to Christianity comes from the first half of the 9th century.

According to the data left by Porphyrogennetos, Emperor Heraclius resettled the Serbs in areas previously devastated by the Avars and subsequently had them baptized by sending priests from Rome. This initial contact did not leave a deep historical mark, and it is believed that while some Serbs were formally baptized by Roman priests, they did not sincerely or permanently embrace Christianity. This was only the first attempt at the Christianization of the Serbs.

Mass Christianization can be discussed only after the baptism of the ruling family. As already mentioned, the first record of a Serbian leader converting to Christianity dates back to the first half of the 9th century. The final Christianization occurred during the reign of Mutimir and his brothers in the second half of the 9th century. It was during this period that Christian names first appeared among the Serbs, specifically with the sons of Prince Mutimir, Petar Gojniković and Stefan.

The Christianization of Serbia took place when Mutimir and his brothers decided to reach an agreement with Emperor Basil I. The Emperor requested that they adopt the Christian faith, and Latin priests were sent to perform the baptism. The Serbian rulers called upon their subjects to come to the riverbank, where they would be baptized in its waters, and those who refused to accept Christianity and remained loyal to their old gods would be considered enemies of the principality.

Serbian Archdiocese (1219—1346)

Before the formation of the Serbian Peć Archdiocese, the Serbs were divided into several ecclesiastical hierarchies: the Sirmium Metropolitanate, the Salona Archbishopric, Justiniana Prima, the Aquileia Patriarchate, and the Ohrid Archbishopric, which had three dioceses (Raška, Lipljan, and Prizren) where the bishops were Greek.

In the 12th century, Stefan Nemanja succeeded in uniting most of the Serbian territories of the time. A very significant figure in this period of Serbian Orthodox history is Saint Sava. As the youngest son of Stefan Nemanja, he was born with the name Rasto. Even as a child, he showed a strong desire for knowledge and a love for Christianity. At just 16 years old, against his parents’ wishes, Rasto went to Mount Athos, where he became a monk, taking the name Sava. Following his youngest son’s example, his aging father Stefan Nemanja also became a monk, adopting the name Simeon. On Mount Athos, the Serbian monastery of Hilandar was established and later restored in 1198. In order to reconcile with his brothers and to bring his father’s body to the Studenica Monastery, Saint Sava returned to Serbia in 1208. This period of Saint Sava’s life is considered the most fruitful, and it is from this time that the stories still told about him today originated. He traveled through Serbian cities, teaching the people about Orthodoxy, protecting literacy, and promoting piety. Before Saint Sava’s appearance, Serbia was under the jurisdiction of the Ohrid Archbishopric. Saint Sava decided to prepare priests, monks, and bishops and to fully establish the independence of the Church in Serbia.

In 1217, Sava left Serbia again and went to the Hilandar Monastery. From there, he traveled to Nicaea, where the Byzantine Emperor Theodore Laskaris and the Patriarch of Constantinople Manuel Sarantene were located. Saint Sava asked for the independence of the Serbian Church, and his request was accepted. He was consecrated (ordained) as the Archbishop of Serbia in Nicaea, taking the title “Archbishop of the Serbian and Maritime Lands.” This was when Serbia finally achieved the autocephaly of its Church. Afterward, Saint Sava returned to Serbia. In addition to the three existing dioceses, he founded eight more: the Žiča, Zeta, Hvosno, Hum, Toplica, Moraviča, Budimlja, and Dabrova dioceses. Each of them had its seat in a monastery, and the Žiča Monastery was declared the seat of the Archbishopric. Of course, such a major undertaking faced opposition. The Ohrid Archbishopric, led by Dimitrius Homitian, protested, sending a letter to Saint Sava. However, this letter had no significant impact on the survival and development of the Serbian Archdiocese.

Saint Sava’s successors continued to strengthen the ecclesiastical organization, with a significant role played by members of the ruling Nemanjić dynasty, who built monasteries—foundations—and richly endowed them with land and people. Each of the Nemanjić kings founded one or more monasteries. The most important among them was the Hilandar Monastery on Mount Athos, founded by Stefan Nemanja, and later restored and expanded by King Milutin.

The church’s independence also found expression in the cult of Stefan Nemanja—Saint Simeon the Myrrh-streaming, who was proclaimed a saint and celebrated in the biographies written by his sons, Sava and Stefan. Later, the cult of Saint Sava, who was also declared a saint, joined the cult of Saint Simeon.

Serbian Patriarchate (1346—1463)

The development of the Serbian Church entered a new phase with the creation of the Serbian Empire during the reign of King, and later Emperor, Stefan Dušan, as well as the reigns of Dragutin, Milutin, and Stefan Dečanski. In preparation for his imperial coronation, the Serbian Church was elevated to the rank of Patriarchate in 1346, in the presence of the Bulgarian Patriarch, the Archbishop of Ohrid, Serbian bishops, and monks from Mount Athos. At the time, the Byzantine Empire was weakened, which worked to Dušan’s advantage, as he sought to replace the weakened Byzantine Empire with a Serbian-Byzantine Empire. He considered himself the Emperor of the Serbs and Greeks, and for his claim to legitimacy, the Archdiocese had to be elevated to the rank of Patriarchate. This occurred on Palm Sunday in 1346 in Skopje. At the assembly, the Archdiocese was proclaimed the Patriarchate, and the first Serbian Patriarch was Joanikije I. He held the title “Patriarch of the Serbian and Maritime Lands.” Seven days later, on Easter, the Patriarch crowned Dušan as Emperor and his son as King. The dioceses of Zeta, Prizren, Skopje, and Raška were elevated to the status of metropolises, with the Skopje diocese being the highest since Dušan had been crowned there. The Ohrid Archbishopric was given a honorary place, right after the Serbian Patriarchate.

After 1346, as the Serbian Patriarchate expanded its jurisdiction over the newly conquered regions (Macedonia, Thessaly, and Epirus), the Patriarch of Constantinople, Callistus I (1350–1353), decided to react by excommunicating the Serbian ruler, Serbian Patriarch, and other Serbian bishops for appropriating the imperial title and patriarchal dignity, as well as for taking church jurisdiction over the dioceses of the Constantinople Patriarchate in the recently conquered regions. This led to a church schism. Emperor Dušan tried to negotiate reconciliation with the Patriarchate of Constantinople, but his sudden death interrupted these efforts. In 1364, Patriarch Callistus was sent to the town of Ser to meet with the nun Elisaveta to work on reconciling the two Patriarchates, as the threat from the Turks loomed over both Serbia and Byzantium. Callistus died during this mission and was buried by those whom he had excommunicated. Partial reconciliation was achieved with part of the Serbian state ruled by Despot Uglješa Mrnjavčević (who ruled in the area of Ser). The idea of complete reconciliation came from the monks of Mount Athos, who lived and labored together. A delegation of monks, led by Serbian monk Elder Isaija and Hieromonk Nikodim Grčić, first went to Serbia to meet with Prince Lazar and Patriarch Sava IV, and then in 1375 they traveled to Constantinople. The negotiations were successful, and a written decision was made, recognizing the canonical status of the Serbian Patriarchate and lifting the mutual excommunication. Two representatives from the Constantinople Patriarchate were sent to Serbia, where, in the Monastery of St. Archangels in Prizren, they celebrated the Holy Liturgy with the Serbs. The anathema was thus lifted, and the churches reconciled.

With the Ottoman invasions, difficult times began for the Serbian Patriarchate. Due to Turkish conquests and the shifting of the state’s center to the north, church centers also moved. In the 15th century, the Belgrade and Smederevo Metropolises were mentioned. Monastic centers also shifted to the north. The monasteries built by Prince Lazar and his successors are all located in the Pomoravlje and Danube regions. Little historical material survives from this time to track the detailed consequences of the Turkish conquests on the Serbian Church. However, it is clear that many medieval Serbian monasteries were abandoned or lost to history.

The threat from the Turks grew, and after the death of Emperor Dušan, no powerful figure emerged to lead the Serbian state and preserve the vast empire Dušan had left behind. One of the first significant Serbian defeats at the hands of the Turks occurred in 1371 at the Battle of Maritsa, where the Mrnjavčević brothers, King Vukašin and Despot Uglješa, were killed. Uroš died later that same year. The majority of the Serbian lands were united under Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović. On Vidovdan (June 15, 1389), the Battle of Kosovo took place on the Kosovo Field (Gazimestan near Gračanica). The Serbs, led by Prince Lazar, honorably suffered defeat. While this battle did not result in the conquest of all Serbian lands, Serbia became a vassal state to the Ottoman Empire. The Battle of Kosovo thus marks a major turning point in both Serbian and Orthodox history. During this time, sources mention two Serbian Patriarchs: Spiridon and Ephraim. Prince Lazar was succeeded by his son Stefan Lazarević, who received the title of despot. After the Battle of Angora in 1402, Serbia ceased to be a vassal state. The Manasija Monastery, Stefan’s foundation, became the spiritual center of the Despotate. One of the last Serbian despots before the final fall into Ottoman slavery was Despot Đurađ Branković. He refused to accept the union with the Roman Catholics, who had promised military aid in the fight against the Turks. Since the Monasteries of Peć and Žiča were already under Turkish control, the center of the Patriarchate was moved to Smederevo, the last free territory.

Legal Status of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the Middle Ages

Regarding the legal status of the Serbian Church and its relationship with the state in the Middle Ages, it was status in statu, meaning it was a “state within a state.” This meant that the Church had its own legislation, administration, and judiciary. Rulers were not allowed to interfere in doctrinal matters, the election, or the appointment of bishops. The ecclesiastical court, which had authority over clergy, was responsible for the welfare of the sick, beggars, the poor, widows, and orphans, and only the Church’s court had jurisdiction over them. Even 13 articles of Dušan’s Code were related to the Church; some of these articles concerned: the obligation of church marriage, the right of bishops to punish the faithful, and the fight against heresy, among other things. Church possessions could not be confiscated, as they had the status of legal property, guaranteed by the ruler. Additionally, church land had economic immunity, meaning that the people working it were exempt from paying taxes and state obligations.

Besides economic immunity, the Serbian Church in the Middle Ages also enjoyed administrative and judicial immunity. The significance of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the Middle Ages was immense, as it took care of the poor, mediated in state decisions, and had a close connection to the rulers. Churches and monasteries were exempt from military service and paying taxes. The Church had a well-developed charitable activity, providing assistance to the poor and the weak, offering them food, clothing, shoes, and shelter. It encouraged the giving of alms and providing help to those in need. The Church had a strong influence on state affairs beyond the ecclesiastical sphere. This was most visible in the right of church dignitaries to participate in the work of the state assembly and actively influence the most important political decisions. The high clergy had the right to intervene on behalf of the poor and those unjustly persecuted.

Struggle for Survival (1463–1557)

By 1496, the entire jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarchate had fallen within the borders of the Ottoman Empire. The stance of the Turkish authorities toward Christians had a general basis in the Qur’an (dhimmi), but their policy toward specific Christian churches was determined and changed depending on the political situation within their territory and their sphere of interests.

The Serbian Church shared the fate of the oppressed Serbian population (raja). Monasteries, like the common people, were subject to various obligations to Turkish feudal lords and the sultan. The primary forms of state-imposed burdens included military service, land and income taxes (harač), as well as various other taxes that the Turks encountered in the conquered territories (taxes on sheep, pastures, wells), and emergency taxes such as war taxes.

To manage the subjugated Christian population more easily, the sultans allowed religious autonomy for Christian churches but also imposed new obligations on the church hierarchy. Church leaders became community leaders — ethnarchs. The primary function of the ethnarchs was to collect taxes for the sultan and the central organs of the empire.

In the early period of Turkish rule, the position of the oppressed raja was not excessively unbearable, but over time, the violence of Turkish feudal lords against the people and the state’s pressure on the church increased. Among all the obligations, the hardest for the people to bear was the conscription of children and their recruitment into the Janissaries. This was called “blood tax” (danak u krvi).

The Serbian Church shared the fate of its people, and over time, disorganization within the Serbian Church became more pronounced. Thus, the Serbian hierarchy was increasingly replaced by bishops of Greek nationality under the jurisdiction of the Ohrid Archbishopric. By the 1530s, the Ohrid Archbishopric had successfully expanded its jurisdiction over many dioceses of the Serbian Church.

Restored Serbian Patriarchate (1557–1766)

During the general period of disorganization under Ottoman rule, there came a brief respite and even recovery under the Grand Vizier Mehmed Pasha Sokolović (vizier from 1555–1579), who was of Serbian origin. In such circumstances, Makarios, the brother of Mehmed Pasha, was granted a decree by the Sultan, appointing him as the first patriarch of the restored Peć Patriarchate (1557–1571; died 1574). The restored Serbian Church under Ottoman rule received the same rights and privileges that the Turkish Sultan had granted to the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

The Era of Provincial Churches (1766–1920)

Before unification, there were seven completely independent or Serbian ecclesiastical areas dependent on foreign churches:

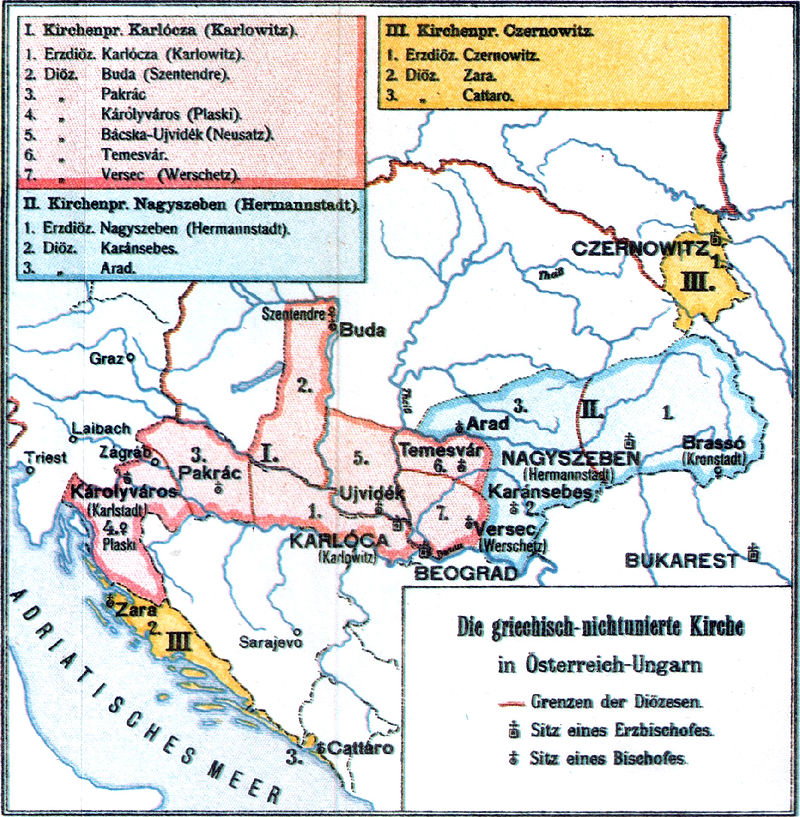

Karlovac Metropolitanate (with seven dioceses) — Covered Orthodox Serbs in Hungary, Croatia, and Slavonia. It was established after the Great Migration of 1690. The name “Karlovac Metropolitanate” came into use after 1713 when the seat was moved to Sremski Karlovci. The history of the Karlovac Metropolitanate represents the struggle of the Serbs to preserve Orthodoxy and survive as a people within the vast Austrian Empire. Notable figures in this struggle were Metropolitan Pavle Nenadović (1749–1768) and Metropolitan Stefan Stratimirović (1790–1836). Serbs in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy survived both as a people and as a Church within that empire.

Montenegrin Metropolitanate (with three dioceses) — Covered the Kingdom of Montenegro. The Ottomans never fully conquered the Serbian tribes in the Montenegrin highlands. In 1712, at the Battle of Cuca, the Ottomans were defeated, and from then on, Montenegro relied on Russia for economic and political support. Montenegro expanded after the wars of 1876 and 1878, when the Zahumlje-Raska diocese was created and the Peć diocese was restored in 1913. Montenegro, like Serbia, gained independence at the Berlin Congress of 1878.

Orthodox Serbs in Dalmatia — The Serbian Church in Dalmatia and Boka Kotorska (with two dioceses). After the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 and the Treaty of Požarevac in 1718, Dalmatia fell under the control of the Venetian Republic instead of the Ottomans. Interestingly, in 1750, despite the Venetians’ bans, the Serbs elected their own bishop. After Napoleon’s conquests, Dalmatia fell under French rule. Only in 1810 did the Serbs get their first bishop. In 1828, the Dalmatian Church came under the jurisdiction of the Karlovac Metropolitanate. In 1867, with the division of Austria and Hungary, Dalmatia and its dioceses (Dalmatian-Istrian and Boka Kotorska) came under the jurisdiction of the Romanian-Ruthenian Bukovina, and this situation persisted until the collapse of Austro-Hungary in 1918 and the unification of the Serbian Church.

Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina (with four dioceses) — After the abolition of the Peć Patriarchate, this church was under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople until the occupation of 1878. Bishops were primarily Greek Phanariots. The position of the Orthodox in Bosnia and Herzegovina was extremely difficult, and despite the Serbian population in the dioceses, the church remained under the supreme authority of Constantinople.

Belgrade Archbishopric (with five dioceses) — Broke away from the Phanariots (Greeks) in 1830 when Serbia became an autonomous principality, and gained full independence from the Patriarchate of Constantinople in 1879 after the complete independence from the Ottomans was declared. In September 1831, the Patriarch of Constantinople, Constantine I, granted autonomy to the Serbian Church. The Prince and the people selected the Metropolitans and Bishops, and the Belgrade Bishop was given the title of Archbishop of Belgrade and the rank of Metropolitan of all Serbia.

Old Serbia and Macedonia (with six dioceses) — This region was also under the authority of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The area of Eastern Serbia (Niš, Pirot, and Vranje) became part of Serbia in 1878. Thus, the churches in this region came under the Serbian Metropolitanate. However, Southern Serbia and Vardar waited for national Serbian hierarchy. In 1912, 1913, and 1919, Greek and Bulgarian bishops left their dioceses, and the Serbian Orthodox Church in Old Serbia and Macedonia joined the Belgrade Archbishopric.

Serbian Church in America — Began to form in 1894 when the first Serbian church was built there, and recognized the Russian Archbishop in New York as its supreme church authority. In 1923, a separate Serbian diocese was founded in Chicago, under the jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarch in Belgrade, and by 1926, it had its own bishop.

From the Unification of Provincial Churches (1920) to Today

Unification and Re-establishment of the Serbian Patriarchate

The First World War ended in 1918. On the ruins of Austro-Hungary and the European part of the Ottoman Empire, new expanded states emerged. The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes was formed for the first time in the history of the Slavs.

The conditions were ripe for the restoration of the former Peć Patriarchate, which had been abolished in 1766. The new state authorities, led by King Peter I, gave their consent, and the Serbian Church approached the Patriarchate of Constantinople, its “Mother Church,” informing it of the new circumstances. The Patriarchate of Constantinople approved the request and issued the appropriate Tomos. Subsequently, an Archbishops’ Assembly was held in Sremski Karlovci, where it was decided that the Serbian Church would be elevated to the status of a Patriarchate.

Before World War II, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia had nearly eight million Orthodox Christians, over 4,000 churches (including chapels and branch churches), nearly 2,500 priests, around 250 monasteries with about 500 monks and 450 nuns (including novices and assistants).

After the end of World War II, the Serbian Church did not receive war compensation. The Communists separated the Church from the state, confiscating about 70,000 hectares of land and 1,180 buildings, valued at eight billion dinars. During World War II, the Serbian Church and its Patriarch Gavrilo (1937–1950) suffered the greatest losses and hardships in its entire history. Through the actions of the UDBA (State Security Service), the so-called American Schism occurred in 1963, when the New Gracanica Metropolitanate was separated from the Serbian Orthodox Church and declared the Free Serbian Orthodox Church. This schism was overcome in 1992 through the efforts of Patriarch Pavle.

In 1969, the self-proclaimed Macedonian Church also split from the Serbian Patriarchate in a similar way. However, it has not been recognized by any of the local Orthodox Churches. After the attempt to resolve the schism in 2002 with the Niš Agreement failed, the Serbian Patriarchate granted autonomy to the Ohrid Archbishopric the same year, and it is now part of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

The breakup of Yugoslavia and the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992–1995), as well as in the Serbian Krajina, brought immense suffering to both the people and the Church. Most dioceses in the western Serbian lands were heavily affected by the war, with the population displaced and churches and monasteries destroyed.

The Dispute Between the Karađorđevićs and Petrovićs

After the liberation of Peć in 1912 and its annexation to Montenegro, King Nikola created the Peć Diocese, subordinating it to the Montenegrin Metropolitan in Cetinje. Such humiliation of the former Serbian Patriarchal center was in complete contrast to earlier statements by King Nikola himself about the necessity of restoring the Serbian Patriarchate in Peć. Although he had the opportunity to achieve this noble goal at that time, the old Montenegrin ruler missed this chance due to his own fault. Only after losing both his crown and state did he attempt to return to his original ideas in exile, opposing the way the Serbian Church unification was carried out in 1920.

The dispute centered around who was the rightful heir to the historical right to the throne of the Serbian Patriarch. King Nikola, in exile, resented the fact that Belgrade elevated the Karlovci Metropolitanate to the level of a pan-Serbian Patriarchate, taking this right away from Peć, to which it historically belonged. Although King Nikola’s aspirations were political, as were those of the Serbian authorities, history was not respected, and the center of the restored Serbian Church was no longer in the Peć Patriarchate but in Belgrade. However, the initiator of such a policy was King Nikola himself, who in 1912 did not honor the historical precedence of Peć, instead favoring Cetinje.

Current Status

The Serbian Orthodox Church is an independent and autocephalous Church with the dignity of a Patriarchate. The seat of the Serbian Church is in Belgrade at the Patriarchal Palace. The head of the Serbian Church holds the title: “Archbishop of Peć, Metropolitan of Belgrade-Karlovac, and Patriarch of Serbia…”

The Church has a total of 39 dioceses and the Ohrid Archbishopric, which consists of one metropolitanate and six dioceses. The Patriarch is the diocesan bishop in the Belgrade-Karlovac Archdiocese. There are four metropolitanates: Zagreb-Ljubljana, Montenegrin-Primorje, Dabar-Bosna, and Australian-New Zealand. There are 35 dioceses: Žička, Šumadija, Šabac, Valjevo, Budim, Niš, Zvornik-Tuzla, Srem, Banja Luka, Timișoara, Canadian, Eastern American, Banat, Bačka, British-Scandinavian, Raška-Prizren, Zahumlje-Herzegovina, Bihać-Petrovac, Osijek-Polje and Baranja, Central European, Western European, Timok, Vranje, Western American, Slavonia, Braničevo, Mileševa, Dalmatia, and Kruševac. Titular bishops exist for the following dioceses: Hvosno, Budimlja, and Jegar.

The Serbian Church today has over 3,500 parishes, 204 monasteries, around 1,900 priests, about 230 monks, and 1,000 nuns.

In terms of church-educational institutions, there are six theological seminaries. Currently, over 1,000 students are studying in these seminaries, and over 1,000 students are enrolled in theological faculties and the Academy.

In addition to these institutions, the Serbian Church established an Academy of Arts and Conservation in Belgrade in 1993, with several departments (iconography, fresco painting, conservation).

As of 2021, the throne of the Serbian Orthodox Church is held by His Holiness, Archbishop of Peć, Metropolitan of Belgrade-Karlovac, and Patriarch of Serbia Porfirije.